Introduction

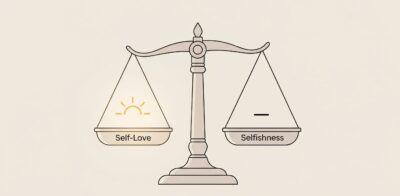

Supplication dynamics reveal the varied ways individuals express their needs and seek support. This article delves into this complex topic by exploring two distinct facets. First, we examine supplication as a sincere plea for help that respects others’ autonomy and resources, ensuring you’re not a burden or prioritizing your needs above theirs. Second, we analyze the darker side: supplication used as a manipulative tactic, where individuals feign extreme helplessness and feebleness to exploit others for personal gain.

This guide will help you recognize these contrasting approaches, understand the subtle balance required, and apply supplication effectively in everyday life without resorting to manipulation. You’ll gain precise definitions, learn actionable cues to maintain moderation, identify warning signs of excess, and encounter vivid, real-life examples. Prepare to transform abstract ideas into clear, practical steps that resonate across cultures and backgrounds.

Table of contents

1. Definition and Components

1.1 What Is Supplication?

- Supplication means openly asking others for help, resources, or compassion in a way that highlights your need.

- It involves vulnerability, as you reveal limits or challenges you face.

1.2 Core Elements of Supplication

- Acknowledgment of Need: You admit you cannot meet a goal alone.

- Request Format: You phrase your ask respectfully and clearly.

- Emotional Transparency: You show genuine feelings—fear, hope, or urgency.

- Contextual Framing: You explain why assistance matters now.

1.3 Sub‑Types of Supplication

- Informational: Seeking guidance or knowledge.

- Instrumental: Asking for tangible help (time, money, labor).

- Emotional: Requesting empathy or moral support.

2. Purpose and Moderation

2.1 Why Practice Supplication?

- Strengthening Bonds: Genuine requests build trust and reciprocity.

- Resource Access: You tap into networks you couldn’t reach alone.

- Emotional Relief: Sharing burdens eases stress and anxiety.

2.2 When to Keep It Balanced

Follow these guiding principles:

- Reciprocity Check: Ensure you give back when you can.

- Proportional Ask: Match the request to the relationship’s closeness.

- Self‑Reliance First: Attempt smaller tasks solo before seeking help.

2.3 Signs of Healthy Moderation

- Clear Limits: You stop once you’ve asked twice or thrice.

- Gratitude: You express thanks genuinely, without expectation of more.

- Mutual Respect: You respect the other’s time and boundaries.

3. Signs of Excessive Supplication

3.1 When Asking Becomes Overuse

Excessive supplication occurs when repeated requests strain relationships or erode personal agency. You cross the line if you:

- Demand Frequently: You ask for help more often than you offer it.

- Highlight Helplessness: You dramatize your need beyond reality.

- Ignore Boundaries: You persist after clear refusals.

3.2 Consequences of Overdoing It

- Relationship Fatigue: Friends and colleagues may withdraw.

- Loss of Credibility: Others doubt your sincerity.

- Reduced Self‑Efficacy: You reinforce belief that you cannot solve problems alone.

3.3 How to Self‑Check

Ask yourself:

- “Have I tried independently?” If not, pause and explore options first.

- “Am I reciprocating?” If you seldom help others, rebalance.

- “Do I respect refusals?” If you push past “no,” adjust your approach.

4. Practical Examples

Below are four realistic, illustrating moderate versus excessive supplication. Each unfolds like a scene, helping you visualize and apply steps in daily life.

4.1 Example 1: Team Project Deadline

Sara works in marketing and faces a tight deadline on June 2, 2025. Instead of emailing every team member multiple times, she:

- Assesses Tasks: She lists her needs clearly.

- Selects Key Contributors: She emails two colleagues with specific requests.

- Offers Support: She promises to review their portions next day.

Because she honored their time and reciprocated, Sara secured help without overburdening anyone. In contrast, a colleague who sent group messages at 8 PM and again at 11 PM, demanding updates, prompted annoyance and minimal response.

4.2 Example 2: Family Loan Request

Aziz needed $500 to cover urgent car repairs. He followed these steps:

- Explored Alternatives: He checked repair quotes and his savings.

- Approached Once: He called his brother, explained the situation respectfully, and asked for the amount.

- Outlined Repayment Plan: He agreed to return the money in two installments by the end of July.

His brother agreed immediately and felt valued. By contrast, another cousin who called daily, expressing panic and guilt-tripping, led the family to refuse further support.

4.3 Example 3: Emotional Support After Layoff

When Lina lost her job on May 15, 2025, she sought emotional support moderately:

- Chose a Trusted Friend: She texted only her closest confidant.

- Scheduled a Call: She asked, “Can we talk for twenty minutes tomorrow?”

- Expressed Gratitude: She thanked her friend before and after the call.

Her friend felt honored to help. Conversely, Lina’s coworker posted emotional pleas on every group chat and tagged colleagues repeatedly. People began to mute notifications and distance themselves.

4.4 Example 4: Community Fundraiser

Rahim volunteered to organize a community fundraiser for clean water. He needed volunteers:

- Created a Sign‑Up Sheet: He shared a clear form with task slots.

- Sent One Reminder: He followed up three days later, thanking those already signed and inviting others.

- Kept Transparency: He posted a schedule and progress updates.

Attendance rose by 40%, and volunteers felt ownership. In contrast, another organizer who sent daily “urgent” emails without details triggered unsubscribe requests.

5. Balancing Supplication Dynamics

- Reflect First: Before you ask, list possible self‑solutions.

- Be Precise: Frame your need clearly and limit follow‑ups.

- Maintain Reciprocity: Offer your help in return.

- Honor Responses: Accept “no” gracefully and adjust plans.

By applying these steps, you navigate Supplication Dynamics with integrity and effectiveness—ensuring your asks build connections rather than erode them.

references

Warning: The provided links lead only to the specified content. Other areas of those sites may contain material that conflicts with some beliefs or ethics. Please view only the intended page.

- Jones & Pittman (1982). “Toward a General Theory of Strategic Self‑Presentation.” In Self‑Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior, Vol. 15. Explores tactics including supplication.

https://books.google.com/books?id=OjxqAAAAMAAJ - Leary & Kowalski (1990). “Impression Management: A Literature Review and Two‑Component Model.” Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47. Reviews help‑seeking as self‑presentation.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34 - Gouldner (1960). “The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement.” American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. Establishes reciprocity in social exchanges.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2092623 - Wikipedia (2025). “Impression management.” Overview of self‑presentation tactics, including supplication.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impression_management - Help‑Seeking Behavior (2023). “Understanding Help‑Seeking in Psychology.” HelpGuide.org. Practical insights on balanced asking.

https://www.helpguide.org/articles/relationships-communication/help-seeking-behavior.htm